August 2018

Review of “Meltdown: Why Our Systems Fail and What We Can Do About It”

20/Aug/18 12:59

Published in March 2018, Meltdown is a book well-worth reading for executives and board directors seeking to better understand why strategic surprises and threats arise faster than ever in today’s economy — and what they can do to better anticipate and adapt to them.

For us, one of the most attractive aspects of Meltdown is that authors Chris Clearfield and Andras Tilscik explicitly confront both complexity and human nature as critical causes of system failure.

They begin with the observation that, as a wide variety of “systems have become more capable, they have also become more complex and less forgiving, creating an environment where small mistakes can turn into massive failures.”

The authors draw on Charles Perrow’s classic 1984 book “Normal Accidents” to explain why this is the case.

As we emphasize in our work at Britten Coyne Partners, Perrow noted how complex systems have many overlapping cause-effect relationships, which in many cases are characterized by non-linearity and/or time delays. In such systems, apparently small causes can have very disproportionate effects.

Perrow further noted how the presence or absence of “tight-coupling” between various parts of a complex system sets the stage for cascading non-linear effects that quickly outpace human operators’ and managers’ ability to understand what is happening and react appropriately.

As Clearwater and Tilczik observe, system “complexity and coupling create a danger zone, where small mistakes turn into meltdowns.”

One obvious approach is to mitigate this risk by reducing a system’s complexity and loosen the coupling between its component parts (i.e., by adding more slack). Unfortunately, the authors note that, “in recent decades, the world has actually been moving in the opposite direction”, with more systems now operating in the danger zone.

Indeed, as we have often noted, that is one of the key consequences of the dramatic increase in connectivity wrought by the internet, as well as increased automation of many decisions and processes.

After providing painful illustrations of various meltdowns that have occurred in recent years, across a wide range of increasingly complex and tightly coupled systems (from the failures of Knight Trading to Deepwater Horizon), the authors arrive at what for us is the book’s most important conclusion: “As our systems change, so must our ways of managing them.”

Too often, organizations focus on risks that are easy to observe, measure, and manage (e.g., “slips, trips, and falls”), rather than the complex uncertainties that pose the most dangerous threats to their survival.

Clearfield and Tilczik then review a number of steps organizations can take to reduce the risk of meltdowns. These included solutions that are familiar to Britten Coyne Partners’ clients, such as Pre-Mortem analyses and other techniques for surfacing dissenting views, and for being alert to the advance warnings of disaster that complex systems often provide in the form of anomalies, near misses, and other surprises that we ignore at our peril.

A powerful and widely overlooked point made by the authors is that, "in the age of complex systems, diversity is a great risk management tool." As they note, diverse teams are less likely to be plagued by the dangers of excessive conformity: "in diverse groups, we don’t trust each other’s judgment quite as much…Everyone is more skeptical…Diversity makes us work harder and ask tougher questions.”

We share Clearwater and Tilczik's final conclusion that putting the solutions they recommend into practice can be tough. Like them, however, we also know from experience that it is not impossible, and have seen the exceptional benefits that that make the extra effort involved well worthwhile.

For us, one of the most attractive aspects of Meltdown is that authors Chris Clearfield and Andras Tilscik explicitly confront both complexity and human nature as critical causes of system failure.

They begin with the observation that, as a wide variety of “systems have become more capable, they have also become more complex and less forgiving, creating an environment where small mistakes can turn into massive failures.”

The authors draw on Charles Perrow’s classic 1984 book “Normal Accidents” to explain why this is the case.

As we emphasize in our work at Britten Coyne Partners, Perrow noted how complex systems have many overlapping cause-effect relationships, which in many cases are characterized by non-linearity and/or time delays. In such systems, apparently small causes can have very disproportionate effects.

Perrow further noted how the presence or absence of “tight-coupling” between various parts of a complex system sets the stage for cascading non-linear effects that quickly outpace human operators’ and managers’ ability to understand what is happening and react appropriately.

As Clearwater and Tilczik observe, system “complexity and coupling create a danger zone, where small mistakes turn into meltdowns.”

One obvious approach is to mitigate this risk by reducing a system’s complexity and loosen the coupling between its component parts (i.e., by adding more slack). Unfortunately, the authors note that, “in recent decades, the world has actually been moving in the opposite direction”, with more systems now operating in the danger zone.

Indeed, as we have often noted, that is one of the key consequences of the dramatic increase in connectivity wrought by the internet, as well as increased automation of many decisions and processes.

After providing painful illustrations of various meltdowns that have occurred in recent years, across a wide range of increasingly complex and tightly coupled systems (from the failures of Knight Trading to Deepwater Horizon), the authors arrive at what for us is the book’s most important conclusion: “As our systems change, so must our ways of managing them.”

Too often, organizations focus on risks that are easy to observe, measure, and manage (e.g., “slips, trips, and falls”), rather than the complex uncertainties that pose the most dangerous threats to their survival.

Clearfield and Tilczik then review a number of steps organizations can take to reduce the risk of meltdowns. These included solutions that are familiar to Britten Coyne Partners’ clients, such as Pre-Mortem analyses and other techniques for surfacing dissenting views, and for being alert to the advance warnings of disaster that complex systems often provide in the form of anomalies, near misses, and other surprises that we ignore at our peril.

A powerful and widely overlooked point made by the authors is that, "in the age of complex systems, diversity is a great risk management tool." As they note, diverse teams are less likely to be plagued by the dangers of excessive conformity: "in diverse groups, we don’t trust each other’s judgment quite as much…Everyone is more skeptical…Diversity makes us work harder and ask tougher questions.”

We share Clearwater and Tilczik's final conclusion that putting the solutions they recommend into practice can be tough. Like them, however, we also know from experience that it is not impossible, and have seen the exceptional benefits that that make the extra effort involved well worthwhile.

Comments

Getting More Out of PEST/PESTLE/STEEPLED Analyses

08/Aug/18 12:42

There probably isn’t anyone reading this who has not been through a strategic planning exercise that attempts to use a structured approach to brainstorm opportunities and threats in an organization’s external environment. These are known by a variety of acronyms, including PEST (political, economic, socio-cultural, and technology), PESTLE (PEST plus legal and environmental), and STEEPLED (PESTLE plus ethical and demographic issues).

Unfortunately, far too many people come away from these exercises feeling frustrated that they have generated a laundry list of issues and related opportunities and threats, but little else.

Having been in those shoes many times over the years, at Britten Coyne we set out to develop a better methodology. Our primary goal was to enable clients to develop an integrated mental model that would enable them to maintain a high degree of situation awareness about emerging threats in a dynamically evolving complex adaptive system – i.e., the confusing world in which they must make decisions.

Our starting point was the historical observation that the causes that give rise to strategic threats do not operate in isolation from one another. Rather, they tend to unfold and accumulate in a rough chronological order, albeit with time delays and feedback loops between them that often produce non-linear effects.

As the economist Rudiger Dornbusch famously observed, “a crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.” The ancient Roman philosopher Seneca observed this same phenomenon far earlier, noting that, “fortune is of sluggish growth but ruin is rapid.”

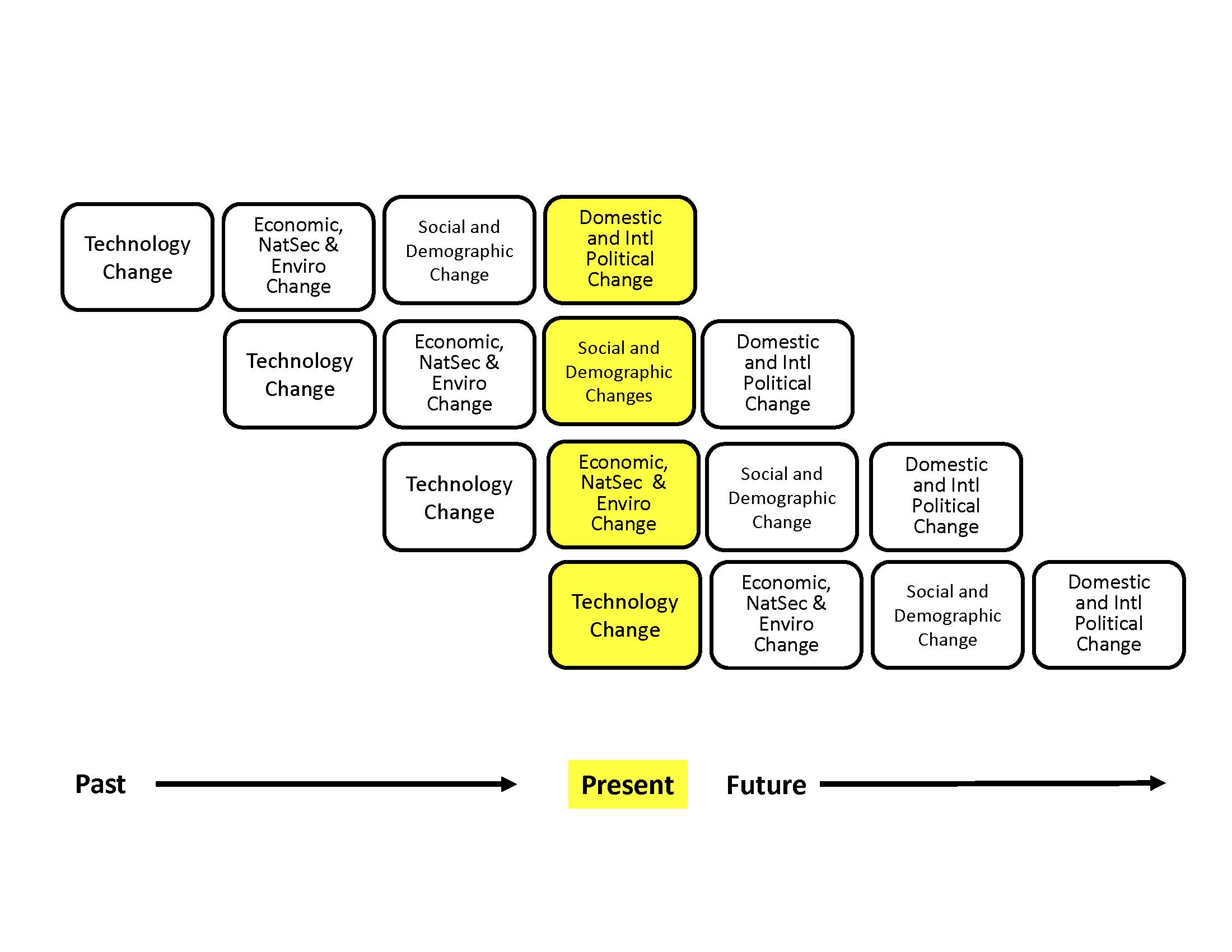

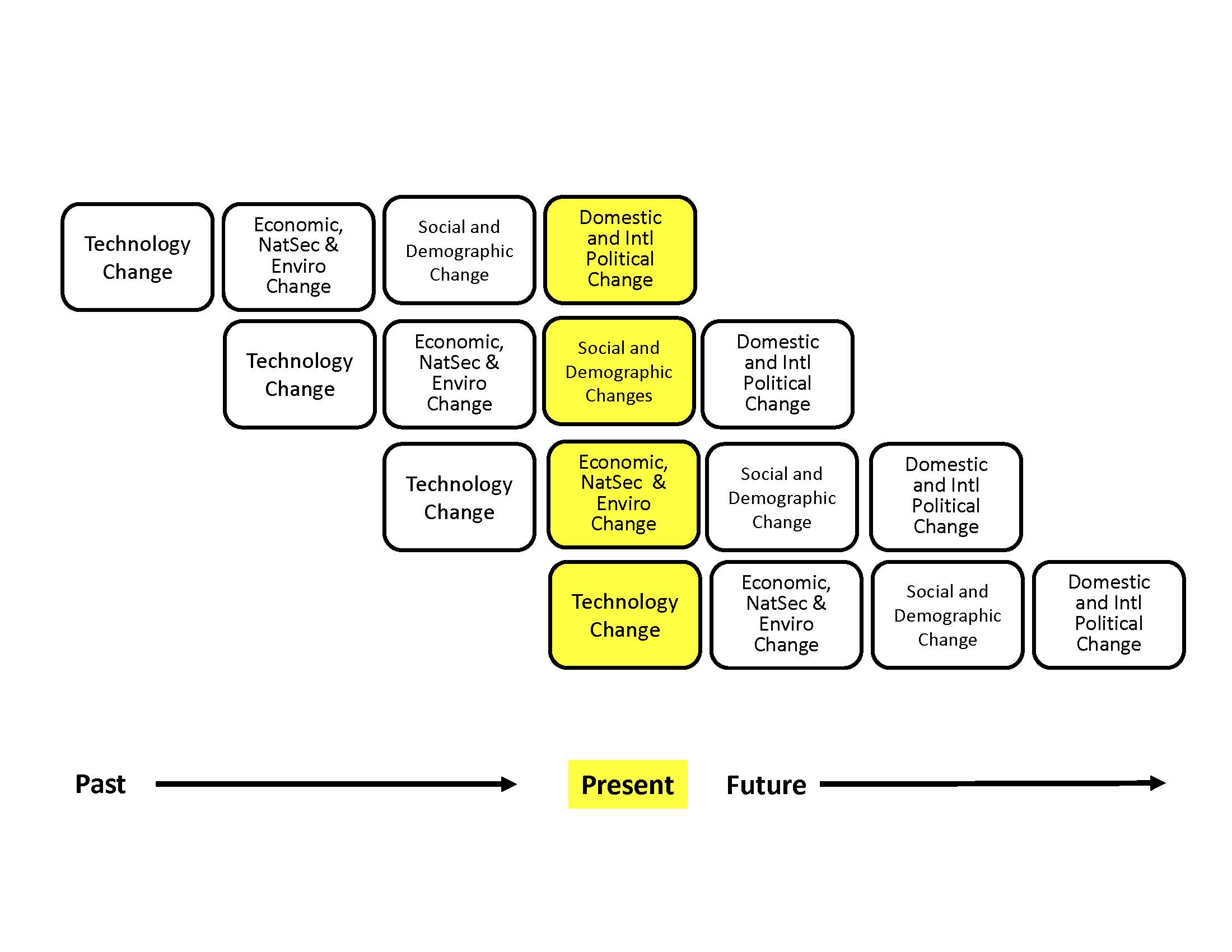

The following chart highlights that the changes we observe in different areas at any point in time are actually part of a much more complex and integrated change process.

In our experience, you develop situation awareness about the dynamics of this system by asking these three questions about each issue area:

With a better (but certainly not perfect) understanding of the key elements in a complex adaptive system, and the relationships between them, you are in a far better position to identify potential discontinuities (and their cascading impacts over time) in order to develop more accurate estimates of how the system of interest could evolve in the future, and the threats and opportunities it could produce.

To be sure, another feature of complex adaptive systems is that due to their evolutionary nature, forecast accuracy tends to decline exponentially as the time horizon lengthens. The good news, however, is that as many authors have shown (e.g., “How Much Can Firms Know?” by Ormerod and Rosewell), even a little bit of foresight advantage can confer substantial benefits when an individual, organization, or nation state is competing in a complex adaptive system.

Unfortunately, far too many people come away from these exercises feeling frustrated that they have generated a laundry list of issues and related opportunities and threats, but little else.

Having been in those shoes many times over the years, at Britten Coyne we set out to develop a better methodology. Our primary goal was to enable clients to develop an integrated mental model that would enable them to maintain a high degree of situation awareness about emerging threats in a dynamically evolving complex adaptive system – i.e., the confusing world in which they must make decisions.

Our starting point was the historical observation that the causes that give rise to strategic threats do not operate in isolation from one another. Rather, they tend to unfold and accumulate in a rough chronological order, albeit with time delays and feedback loops between them that often produce non-linear effects.

As the economist Rudiger Dornbusch famously observed, “a crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.” The ancient Roman philosopher Seneca observed this same phenomenon far earlier, noting that, “fortune is of sluggish growth but ruin is rapid.”

The following chart highlights that the changes we observe in different areas at any point in time are actually part of a much more complex and integrated change process.

In our experience, you develop situation awareness about the dynamics of this system by asking these three questions about each issue area:

- What are the key trends and uncertainties – i.e., those that could have the largest impact in terms of the threats they could produce (or, from a strategy perspective, the opportunities)?

- What are the key stocks and flows within each area? This systems dynamics approach focuses attention on one of the key drivers of non-linear change in complex adaptive systems – accumulating or decumulating stocks (e.g., levels of debt or inequality, or the capability of a technology) that reach and then exceed the system's carrying capacity. While media attention typically focuses on flows (e.g., an annual earnings report or this year’s government deficit), major discontinuities in the state of a complex adaptive system are often caused by stocks reaching a critical threshold or tipping point.

- What are the key feedback loops at work, both within each area, and between them? Positive feedback loops are especially important, as they can cause flows to rapidly accelerate and quickly trigger substantial nonlinear effects both within a given issue area and often across others as well.

With a better (but certainly not perfect) understanding of the key elements in a complex adaptive system, and the relationships between them, you are in a far better position to identify potential discontinuities (and their cascading impacts over time) in order to develop more accurate estimates of how the system of interest could evolve in the future, and the threats and opportunities it could produce.

To be sure, another feature of complex adaptive systems is that due to their evolutionary nature, forecast accuracy tends to decline exponentially as the time horizon lengthens. The good news, however, is that as many authors have shown (e.g., “How Much Can Firms Know?” by Ormerod and Rosewell), even a little bit of foresight advantage can confer substantial benefits when an individual, organization, or nation state is competing in a complex adaptive system.